Today is Bastille Day, the 223rd anniversary of the storming of the Bastille prison, much to the annoyance of the seven elderly prisoners being held there. To commemorate the day, I had two options. I could either build a barricade or do a blog post. Well, I'm slap out of cobblestones and extra furniture, so here's a blog entry tangentially related to the French Revolution. It's my undergraduate thesis. (With pictures!)

Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite,

Callie R.

Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite,

Callie R.

French society was in a state

of near-constant turmoil in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In a culture where women were inevitably

barred from the processes of political decision making, they instead made use

of popular political symbolism, charging even the seemingly innocuous realm of

high fashion with revolutionary sentiments.

The events surrounding the Paris Commune gave rise to several sudden and

striking shifts in the fashionable woman’s silhouette. The most startling

change in high fashion to trace its popularity to the Commune was the bustle

skirt. Beginning in the late 1860s,

previously circular hoops became more ovoid, and a slight padding was added at

the back of the dress. However, in 1870

and 1871, skirts deflated dramatically and became more cylindrical. The hoop skirt and previously ubiquitous

crinoline disappeared in a matter of months. The reasons for this rapid evolution of fashion were manifold: the circumstances of

the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune created a climate of intense

political upheaval; the Communards purposely embraced Jacobin symbols

associated with the Radical Revolution and the Terror; and the varying

depictions of women during the Commune forced the women of fashionable Paris to

adhere to often incompatible standards.

Prior to the outbreak of the

Franco-Prussian War, the upper echelons of French society relished the opulence

of the Second Empire. The reign of Napoleon

III was, for the wealthy, a time of economic prosperity and peace.[1] After sixty years of relatively austere

dress, bourgeoisie women again felt secure enough to dress themselves in

elaborate costumes, rivaling those of the ancien régime. Bright colors, often made by new,

artificial dyes, were generally the most popular: bright violet, pink, green,

glossy brown, and yellow.[2] In the earliest years of the Empire, from

approximately 1852 to 1856, shades of pink and blue were the most common, often

on gowns made of delicate moiré silk.[3] By the end of the decade, mauve and rose,

still rich, but more subdued, were the prominent colors, and fabrics were more

sumptuous.[4]

| Empress Eugenie and her Ladies |

The most recognizable feature of

Second Empire couture was, without a doubt, the crinoline. Skirts became fuller between 1852 and 1855,

and were trimmed delicately, with lace or velvet ribbon.[5] At this point, however, even the most

elaborate gown could be supported by a simple hoop skirt, a bell-shaped cage

typically made of whale bone, willow branches, or steel.[6] By the mid-1850s, the crinoline, a stiff,

layered underskirt made of horsehair, was added in order to support the

increasing diameter of the skirts.

Despite the crinoline’s ubiquitous presence in fashion plates, it was

not without controversy, due to its impracticability and its aesthetic value. Octave Uzanne, a nineteenth century fashion

writer, claimed it was a point of serious contention among ladies, and, despite

his tongue-in-cheek tone, he acknowledged the importance of fashion in France

and the passionate opinions of his fellow citizens and citizenesses. He stated, “No Frenchman was more

passionately absorbed in any political question than were his fellow

countrywomen in the discussion on the crinoline.[7]”

| 1853 |

| 1854 |

| 1857 |

| 1858 |

| 1860 |

| 1862 |

The full skirts popularized by

the Empress Eugénie, Napoleon III’s wife, and Princess Pauline von Metternich,

the wife of an important Austrian diplomat, sometimes measured as much as nine

feet in diameter and required up to 1100 yards of material.[8]

This elaborateness of dress was more

extreme than even the famous robes à la francaise, worn by Marie

Antoinette and ladies of the French Court.

In times of political unrest, both styles were viewed negatively, as

symbols of over-indulgence and excess, and were quickly abandoned as a matter

of political prudence.

By the late 1860s and the end

of the Empire, the French economy had begun to slow and Napoleon III’s

popularity was waning.[9] The bourgeois fixation on the ostentatious

was less pronounced, and the crinoline had begun to shrink. Gowns could typically again be supported by

starched petticoats or hoops. The gaiety of dress that had already begun to

fade by the late 1860s “fled in a trice, and [was] replaced by a sort of

concentrated seriousness bordering on remorse, and a simplicity of dress that

almost savored downright poverty.”[10] Even before the fall of the Empire, popular

opinion was beginning to turn against the excesses of the Court, and especially

the glamorous Empress Eugenie. Beginning

with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, dress became more modest,

particularly around the neckline, and materials became less extravagant.[11] During the siege of Paris, citizens of all

classes were reduced to near starvation, creating a sense, if only for a brief

moment, of solidarity. In an etching

done in 1877 but based on sketches made in 1871, a bourgeois woman wearing a fichu

and robe à la polonaise collects money from men in working class

garb.[12]

| 1864 |

| 1867 |

| 1869 |

If the gowns of the Second

Empire were symbols of extravagance and wealth,

the fashions of the Paris Commune represented grief and unity. The color red was emblematic of the

Commune. Seen as the color of

revolution, the Commune’s flag was solid red, and its supporters wore red sashes

and scarves.[13] Marianne, the allegorical embodiment of

French republicanism, was most often depicted wearing red, or at least the infamous

bonnet rouge, the peaked Phrygian cap first worn by freed Roman slaves. Le Moniteur de la Mode advocated in

April 1871 wearing street clothes of black or another dark color. Anything bright would be in poor taste. Dark purple, grey, brown, black, and white

were, according to contemporary magazines, overwhelmingly the most popular

colors in spring of 1871.[14]

| 1871 |

Crêpe, a crinkled, gauzy fabric, which

was widely used in dresses of the era to symbolize mourning, soon took on a

patriotic meaning. The citizens of Paris

flew tricolor banners and drapes, often made out of the lightweight fabric.[15] After a time, the use of the material became

associated with flying the tricolor flag and a degree of patriotism. Domestic textiles became popular and, though

perhaps out of necessity, wearing “extremely fine French cashmere” and other

decidedly non-exotic materials, was considered patriotic and fashionable. This was a far cry from the days of the

Second Empire, when clothing made in and influenced by French colonies and

allies was desirable.[16]

| Dog and Cat Butcher |

The political turbulence and immense

hardships that began in 1870 were perhaps the most critical factor in the rapid

evolution of women’s fashion. On 15 July

1870, Emperor Napoleon III entered into a disastrous war with Prussia, over the

matter of succession to the Spanish throne. The Prussian chancellor, Otto von

Bismarck, had been attempting to draw France into war since 1868.[17]

Prussia was well-prepared for the

conflict: German Confederation troops numbered over 800,000. Comparatively, the French had only 360,000.[18] The fighting culminated in the Battle of

Sedan and the capture of Napoleon III and his armies, on 2 September 1870. On 4 September, crowds gathered peacefully at

the Place de la Concorde and the Hôtel de Ville organized and declared the Third

Republic, with General Louis Trochu as its interim president.[19]

Although the Second Empire collapsed

unexpectedly after Sedan, the provisional republican government took control

with relative ease. Prussian troops

arrived outside Paris in mid-September 1870, and laid siege to the city.[20] Parisians held out for five excruciating autumn

and winter months, as provincial armies tried and failed to drive away the

German Confederation’s forces. At the

beginning of the siege, Trochu estimated the city could sustain itself for

eighty days, and Parisians attempted to carry on as normally as possible. They communicated with the outside world via

pigeon and balloon, until prolonged rains, cold weather, and shorter days made

balloon flights impossible and pigeons unreliable.[21]

The atrocious conditions in

the besieged city of Paris led to a sense of socio-economic solidarity. While conservative French politician Adolphe

Thiers conducted inconclusive armistice negotiations with Bismarck, conditions

in the capital continued to deteriorate.

By December 1870, people of all classes had taken to eating horse, dog,

cat, and rat meat.[22] An engraving from early December depicts an

auction at the fish market. Men and

women are crowded together, bidding furiously for no more than a half-dozen

tiny fish. On the front row, amongst the

peasants and grisettes, an elegantly dressed young woman, with a lace

cap and ruffled robe à la polonaise stands calmly with an empty basket.[23] In a similar vein, newspaper etchings showed

the wealthy and commoners standing together in a butcher shop line. One 1871 illustration shows a “boucherie

canine et félin.” In the left

foreground, a woman in fur and a polonaise and a young man in a waistcoat and

top hat are sadly bringing their dogs to be slaughtered. On the right, two rough peasants look sadly

on their small puppy.[24] The exceptionally wealthy dined on

slaughtered zoo animals.[25]

Wine consumption tripled among

inhabitants, in an attempt to increase caloric intake, and dried albumin was

used as a substitute for eggs.[26] The winter was colder than average, seldom

reaching above freezing.[27] Flooding caused epidemics of typhoid, and

smallpox was rampant.[28] The death toll in October was ten times

higher than average. By January 1871, nearly 4500 Parisians were dying every

week, and infant mortality was close to ninety percent.[29]

| A fish auction, note the upper class woman |

| I'll let you run this through Google Translate by yourself. Go ahead. I'll wait. |

The Prussians began shelling

the capital in early January 1871, and talk of revolution in the crippled city

became more serious, as citizens grew angry over the government’s inability to

lift the siege.[30] On 28 January, Thiers capitulated to the

German armistice terms: Napoleon III’s disgraced army was to be exiled to

Switzerland until the peace treaty was signed and ratified. A 200 million franc indemnity had to be paid

by the city of Paris. The German

Confederation annexed the territories of

Alsace and most of Lorraine, with a combined population of 1.6 million, and

German soldiers paraded through the streets of the defeated city.[31] National elections for the new republic were

held only a fortnight after France’s surrender, primarily in an attempt to

stabilize and legitimize the young government.

However, circumstances were far from ideal, as nearly half a million

otherwise eligible citizens were disenfranchised by their status as prisoners

of war or refugees. Germans still

occupied many parts of France, and voting was hindered in those areas.[32] Voters in unoccupied territory were eager to

see the war end, and overwhelmingly supported Thiers. Additionally, monarchists won well over half

the seats in the National Assembly.

Thiers was elected president,

despite finishing twentieth out of forty-three candidates in Paris. The treaty was ratified overwhelmingly, and

six Parisian representatives resigned in disgust. This sense of outrage was shared by their

constituents, and by mid-February, the newly-formed Central Committee of Paris

was discussing autonomy. Seemingly in

anticipation of unrest, the Committee moved the 400 cannons, purchased to

defend the outskirts of the city during the siege, closer to the city center.[33]

Whether deliberate or not,

Thiers and the Assembly provoked the citizens of Paris with a series of harsh

policies. In early March 1871, he ended

the wartime moratoriums on rent and bills, despite the fact that the city was

nowhere near economic recovery. He chose

Versailles, rather than Paris, as the new government’s permanent home. Not only did Parisians feel slighted by the

move; the monarchist-led Assembly’s choice of the former royal palace as its

seat made many fear another attempt at a Bourbon restoration.[34] The new government cracked down on dissenters:

several popular left-wing newspapers were shut down, and some popular labor

leaders were tried and sentenced to death in absentia.[35]

The final blow came on 18 March

1871, when Thiers’s troops made an unsuccessful attempt to remove the cannon

from the Montmartre.[36] Though it was not declared officially until

28 March, the short-lived but bloody experiment known as the Paris Commune

began.[37]

| The French, doing what they do best. |

The Communards adopted the old

Republican calendar used during the First Republic, and a solid red flag. They implemented a policy separating church

and state, reinstated the wartime debt remissions Thiers had ended, abolished

night work in bakeries, established a pension fund for the unmarried lovers and

children of slain National Guardsmen, and established a policy of workers’

self-management.[38] Fighting between Republicans and Communards

began in earnest on 2 April 1871, although the Commune’s attempt to march on

Versailles the next day failed.[39] While neither side sought to escalate the

conflict, neither did either party express willingness to negotiate. Most famously, the Communards pulled down the

Vendôme Column, a monument to Napoleon Bonaparte, in the hopes that the action

would generate international support.

However, the national government successfully controlled the information

coming from the rebellious city, and the hoped-for support never came.[40]

| The infamous French Republican Calendar makes a return |

Throughout April and May, the

government forces grew in size, as returning French prisoners of war were

turned over to Thiers.[41] On 21 May 1871, a gate in the city’s western

wall was inadvertently left open and unmanned, allowing national troops to

reenter the city of Paris, where they were welcomed by the bourgeois residents

of affluent western neighborhoods.[42] The Communards were badly outnumbered and

lacked a centralized command or plan.

Each barricade was commanded by a local leader, with little

communication between them.

Additionally, the widening and repaving of Paris streets, undertaken by

Baron Haussmann in the previous decade, made building barricades in the streets

extremely difficult. As national troops

maneuvered to outflank Commune barricades, they slaughtered many

civilians. Though the Communards made

repeated attempts to arrange an exchange of hostages, Thiers refused, and both

sides executed many of their prisoners.[43]

By the last week of May,

nearly all of the barricades had fallen.

The few that remained were centered around the Parisian slums. Despite the efforts of rebel fighters, the

last barricade fell on the evening of 28 May.[44] The same night, national troops executed 147

Communards in Père Lachaise cemetery, thereby ending the semaine sanglante, or

Bloody Week.[45] Tens of thousands of Parisians were arrested

for their involvement with the Paris Commune.

Estimates for the number of Parisians killed during and immediately

after the Commune vary wildly. The

figure likely fell between 30,000 and 50,000: just as many, if not more, than

were killed during the Reign of Terror. Conversely,

the Versaillais troops suffered fewer than 1200 deaths and disappearances.[46]

| Dead Communards |

Precedents set by the French

Revolution established the symbolic power of high fashion, and the parallels

between Terror and Commune were not lost on the bourgeoisie. The robe à la francaise was synonymous

with the French Court at Versailles and the decadence of the French monarchy.[47] Made with yards of silk, the robe à la

francaise was an elaborate update of the robe volante, or sack

dress, popular in the mid-eighteenth century.[48] The bust was funnel-shaped, and the skirts

were wide and rectangular. The skirts

were opened in the front, in order to display an intricately decorated

underskirt. The complicated box pleats

down the back, the elaborate embroidery, and the robings, or skirt decorations,

ensured the robe à la francaise was worn only by the wealthiest ladies

of the Second Estate.[49]

Robe a la francaise, 1765, Robe volante, 1730s

The robe à l’anglaise was

cut similarly, but with a fitted back instead of box pleats, and was often

nearly as ornate. It was, however,

extremely popular in the early stages of the Revolution, usually worn with a

thin triangular shawl, known as a fichu, imitating the pastoral costumes

of the paysannes, or French peasant women.[50] Following the arrest and execution of Louis

XVI and Marie Antoinette, the robes à la francaise and robes à

l’anglaise disappeared entirely. A

symbol of loyalty to the ancien régime and the monarchy, such opulence

was dangerous. Instead, women began to

wear the robe en gaulle, better known as the chemise dress.[51]

A fashion plate from Le

Moniteur de la Mode, dated April

1871 depicts a woman wearing two layered skirts. The first is of French

cashmere. The second is of English crepe, cut on the bias to resemble the skirt

of a peasant and worn long in the back, to allow ample material to drape.[52] This style of dress is known as a robe à

la polonaise. First popular among

French courtiers during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, it had a

distinctly pastoral look, and resembled dresses worn by paysannes.[53] The dress consisted of a very full skirt and

a fitted bodice. The skirt was rigged so

that it could be ruched or gathered in the back. Hooks and rings, cords and buttons, or simple

ribbon ties were used to adjust the skirt.[54] While it began as a novelty among ladies of

the French Court, during the Revolution it became a safety device. Adding cords or ribbons to tie up an overly

full skirt was a simple alteration, but meant the difference between the Second

and Third Estates. For similar reasons,

the robe à la polonaise became popular in 1871.[55] Though the bourgeoisie was not persecuted

specifically during the Commune, the violence of the era matched, if not

surpassed, the violence of the Terror.

There was an additional social pressure to adapt more austere styles,

and work alongside women of all classes and occupations was seen as a patriotic

duty.[56] Thus, the gown of the Second Empire could

easily become a robe à la paysanne.

Robe a la polonaise: 1871 and 1793

At their most opulent: 1750 and 1860

At their most austere: 1793 and 1872

In the late 1860s, Paul Klenck

produced a series of caricatures called The Imperial Menagerie, including

a scathing drawing of the Empress.

Entitled “La Montijo,” a reference to her Spanish surname, it depicts

Eugénie as a gypsy madwoman.[57] Her dress is opulent, though shown as a short

dancing costume. It also makes an oblique

reference to the excesses of the ancien régime: Eugenie’s dress is shown

as a robe à la francaise, with a pointed bodice and wide skirts. The London

Illustrated News published an engraving on 17 September 1870, depicting a

parade of French citizens celebrating the declaration of the Third

Republic. The parade is led by four

women, dressed in clothing typical of the Revolution. One woman wears a Pierrot bodice, one wears

an apron, one wears a robe en gaulle. They all wear tricolor cockades,

and their clothes are striped.[58] They resemble more closely the woman in the

1792 fashion plate entitled “French Women Who Have Become Free” than the

fashion plates of the Second Empire.[59]

|

| Not the same etching cited above, but similar, from 1870 |

|

| French Women Have Become Free, 1792 fashion plate |

The leaders of the Paris Commune saw

their work as a second French Revolution.

They embraced the Jacobin influence with enthusiasm, despite its

association with the Reign of Terror. They

adopted the Republican calendar, first used from 1793 to 1805, and associated

with Robespierre’s attempts to secularize the calendar and redefine every

possible aspect of French life. A series

of caricatures by Paul Klenck, published during the Commune, depicts many of

its leaders in a Jacobin light. Paschal

Grossuet, a journalist and one of the leaders of the Commune, is shown holding

a red quill and ink pot. His body is

covered with a red-tinted copy of La Bouche du Fer, a popular left-wing

newspaper, published during the early days of the Radical Revolution.[60] Frederic Cournet, the leader of the National

Guard at Montmartre, is dressed in red, white, and blue, and wearing the

clothing of a sans-culottes, the radical working class men who formed the

original Paris Commune.[61] Felix Pyat, a Socialist leader, is also

dressed as a sans-culottes, and has the phrase ‘le vengeur’ inscribed on

his cap.[62] In a cartoon critical of Père Duchêne,

one of the two major pro-Commune newspapers, an issue of the paper is on a

table, and a bloody severed head rests on top of it, a quill tucked behind its

ear. The caption read “The True Père

Duchêne.” The cartoon implies that

the words of the Communards are written in blood, and not in ink, while calling

to mind images of the Terror and the guillotine.[63]

| The Guillotine Burns. Somehow, this did little to assure upper class Parisians. |

Although most prominent Communards

did not call for class warfare, some did, and their rhetoric was met with

enthusiasm.[64] Many Communards echoed the anticlerical

attitudes of their revolutionary predecessors, and false reports describing

massacres of priests, nuns, friars, and bishops were often picked up by

anti-Commune and sensational journals.[65] Perhaps most frightening to the upper class

Parisians, leading Communards formed an executive committee of five men, and

named it the Committee of Public Safety, after the Jacobin group formed by

Robespierre in 1793.[66]

Despite the Commune’s promise of

universal suffrage, women were excluded from official work. Instead, they formed vigilance committees,

gave public orations, pursued their own radical agendas, and fought on the

barricades during the Bloody Week.

Although they were forbidden to participate in any formal capacity, the

women of the Commune were by equal turns idealized and villainized, and female

images proved to be the most iconic of the Commune’s brief existence.

Marianne, the traditional

emblem of French republicanism, was depicted in many, often contradictory,

ways. She was by equal turns Amazon and

Vestal virgin, victim and aggressor, lover and warrior. She was at times seen as synonymous with all

of France, but often the two were separated.

Famed illustrator Gustave Doré depicted Marianne in 1870 as a republican

Joan of Arc figure.[67] She wears white robes, a white Phrygian cap,

carries a banner and sword, and leads a column of French troops. Klenck again depicted the stylishly dressed

Empress Eugénie, this time fleeing Paris after her husband’s defeat at

Sedan. She is chased by a furious

Marianne, wielding a broom, as opposed to her traditional flintlock or

tricolor.[68]

In the devastating aftermath of the

war, France was depicted almost exclusively as a victimized woman. In one 1871 lithograph, she lies in full

Classical regalia, on top of her shield, while Albion (dressed as Neptune, god

of the sea) looks on, sneering.[69] Daumier depicted her half nude in an

operating theatre, waiting to be butchered by the new National Assembly.[70]

In still another, she was depicted as a

Lucretia-figure, nude from the waist up, being butchered by Thiers.[71]

| Marianne as Victim |

However, this imagery evolved

immediately upon the founding of the Commune.

Daumier depicted Marianne with her traditional robes and Phrygian cap in

April 1871. In his illustration “The Chariot

of State,” she and Thiers were depicted driving the same cart, with horses

running in different directions, associating Marianne with Paris and the Commune,

not with France or the official Republican government.[72] This shift in symbolism was repeated

throughout the life of the Commune.

Another illustration depicted a relatively bourgeois Marianne in a solid

red bustled dress, bonnet rouge, and with breasts nearly exposed. She wears an anchor-shaped pendant around her

neck, likely an allusion to the broken chains found in more classical

representations. She watches warily as a

smirking Thiers, dressed as a cobbler, repairs a dainty red high-heeled boot. The

caption reads, “Ha! I will fix it so this one does not have the power to walk

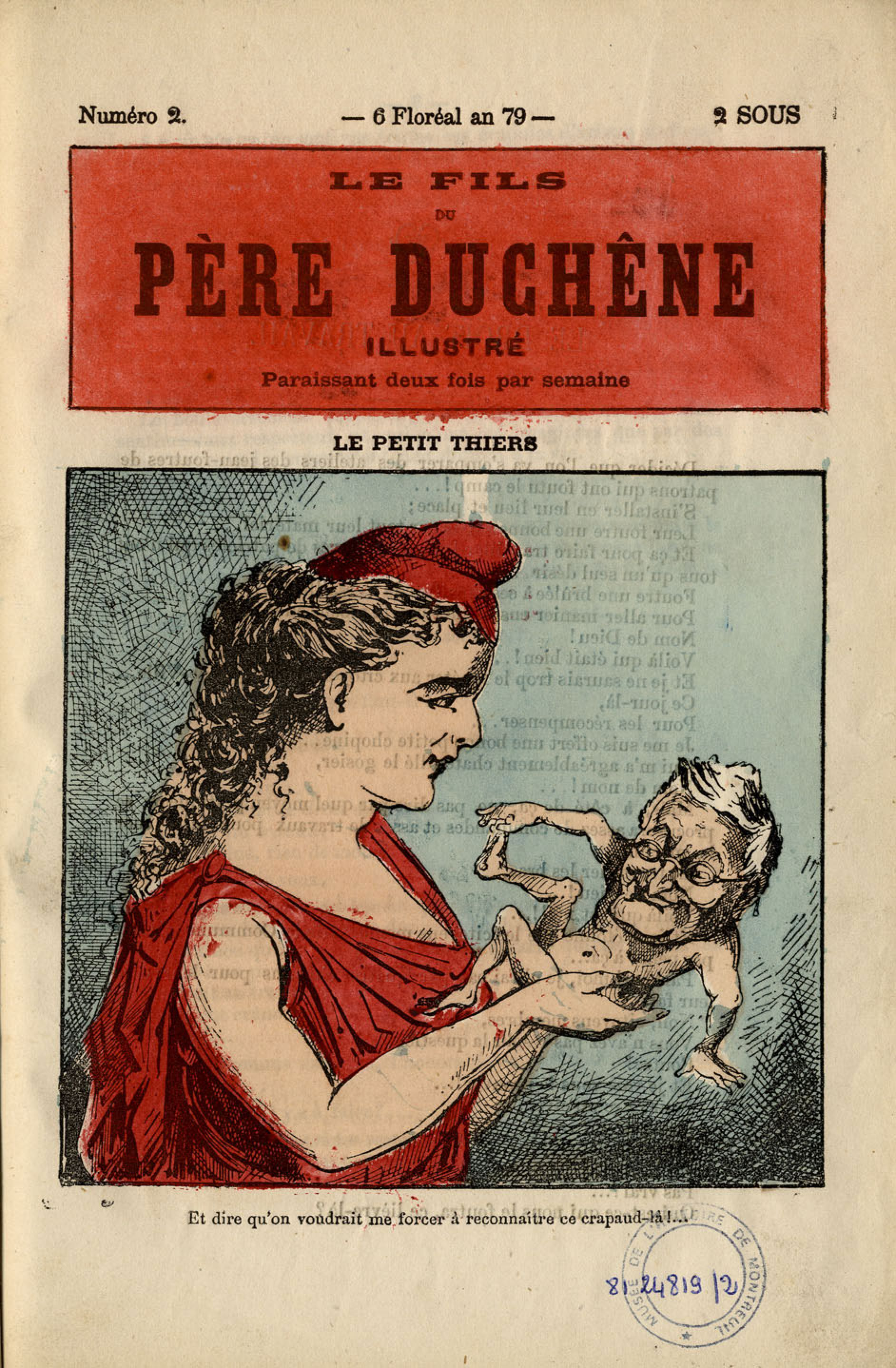

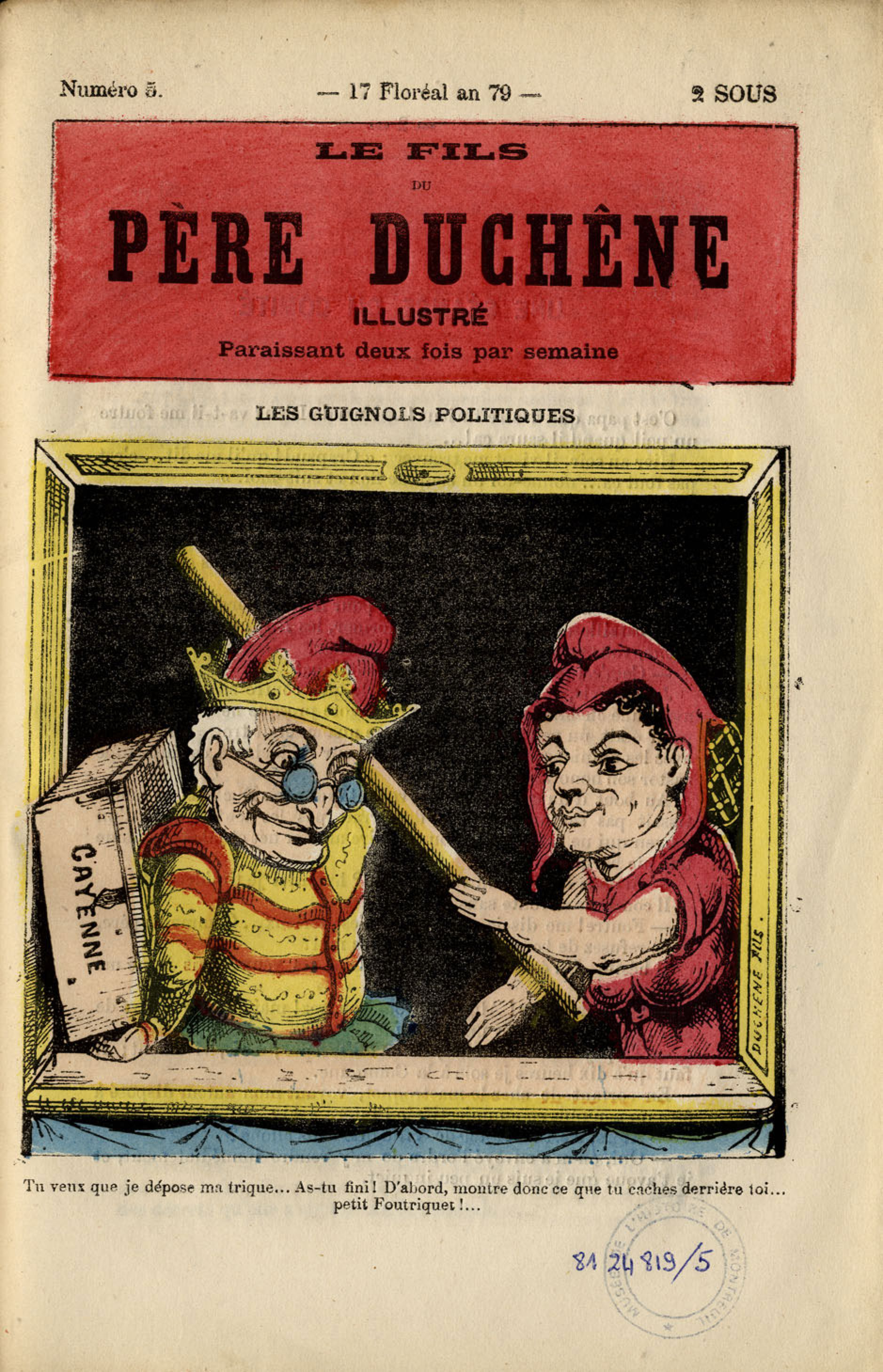

anymore!”[73] Le Fils du Pere Duchêne, an ardently

pro-Commune satirical magazine depicted Marianne in wildly differing roles. The magazine printed ten issues, and Marianne

was on six of the covers: as a reluctant mother, an aggressor puppet, a

victimized puppet, a Classical bust, a bourgeois woman, and a courtesan leaving

her lover.[74] This illustrates not only the importance of

Marianne as a symbol of the Commune, but also her malleability.

When the Commune fell, the

Third Republic reappropriated Marianne as a symbol. Doré satirized this by depicting Marianne as

a corpulent woman, barefoot, with a Phrygian cap, carrying her trademark

flintlock rifle in one hand and butcher knives in the other. Her breasts are covered, but bulging in her

too-tight robes, and her bonnet rouge is topped with a halo.[75] Daumier produced a series of grim takes on the

image of the French ideal. “The New Year” showed Marianne without her red cap,

wielding a broom, and sweeping up debris, including a bucket labeled “pétrole.” The illustration bore only the caption

‘1872.’ In another, he depicted her as a

skeleton, seated on the remains of a barricade, still draped in her robes, but

wearing a coquettish hat and playing the horn.

It was a satire of the hopeful and idealized depictions of Marianne that

began to appear in 1872. Finally, he

showed her as an emaciated corpse, in her robes and cap, lying in a

coffin. The caption read, “And all the

while, they insist she has never looked better.”

Female supporters of the Commune

were known as Communardes, and despite the lack of official female standing,

women played an integral role in the Commune.

From radical and highly visible activists like Louise Michel to

anonymous supporters, the Communardes provided a striking image in the public

imagination. They were depicted in

neutral or positive cartoons as being beautiful young women, wearing

militaristic boots, trousers, and bodices, with the simple skirts and aprons of

the working class.[76] Another etching published in London soon after

the fall of the Commune showed young women in upper class finery examining the

bodies of fallen street fighters. One

appears in full mourning, the others in demi-deuil, or

half-mourning. Two wear bustles and one

a polonaise, and their hats resemble Marianne’s Phrygian cap.[77] Similarly, an etching titled “The Triumph of

the Monarchy” depicted a skeletal and classically robed Death crowning Thiers

with a laurel wreath, atop a ruined barricade.

At their feet, lower and middle class women tend the wounded and mourn

the dead.[78]

Other accounts of the Communardes were

more scathing. Georges Clemenceau

described their “blood lust,” and likened them to “wild beasts.”[79] Many men proposed theories attempting to

explain the supposed behavior of the Communardes. Some suggested that they were, by nature,

more excitable and mentally weaker. Others

claimed they were evil and unnatural.

Alexandre Dumas, fils, referred to them as femelles, a

term used to describe female animals. He

claimed they resembled women only when they were dead.[80] Many assumed the Communardes were

prostitutes; others referred to the women in Classical terms, calling them

hecates, furies, harpies, and Amazons.[81] A lithograph called “The Defense of the

Commune” shows a woman in a Phrygian cap, wearing a short and tattered

tunic. Her right breast is bared, an

allusion to both the Virgin Mary and the Amazons. She stands on a barricade wielding a blade,

while other traditionally-dressed women kiss their lovers and tend to the wounded.[82] She is depicted much like an Amazonian

Marianne, however, and not as a loathsome pétroleuse.

Conversely, the popular image of the

pétroleuse was seized upon by the Versaillais for use in their

anti-Commune propaganda, and no image of the Commune captured the same place in

the public imagination. The pétroleuse,

a female arsonist, is almost certainly a creature of myth. Massive fires occurred in Paris, beginning in

earnest on 23 May 1871. The most

infamous casualty of the fires was the Palais des Tuileries, but entire suburbs

of Paris, financial buildings, the Hôtel de Ville, the Louvre, the Palais de

Justice, several theatres, and the docks at La Villette were burned, among many

other structures. The Versaillais likely

started the first fires on 22 May; the Communards were responsible for most of

the others, although supporters of the Commune also saved many structures,

including the National Archives and Notre Dame.[83] It is has thus far proven impossible to

determine the origins of the mythical pétroleuse.[84] Contemporary newspaper illustrations showed

the havoc wrought by the female arsonists, as well the execution of pétroleuses,

often dressed in flowing black, appropriating elements from the costumes of

both Marianne and Death.[85] Regardless of whether women were really

setting fires, and regardless of whether any pétroleuses were ever

actually executed, the press gave its readership the distinct impression that

it was happening with alarming frequency.

And though many drawings of the women depicted grotesque and androgynous

hags, several written accounts describing pétroleuses taken prisoner by

the Versaillais noted that there were women of all ages and social classes

among the accused.[86]

Although it first appeared in the

year prior to the Franco-Prussian War, the bustle skirt’s rapid ascent to the

realm of haute couture can be traced to the circumstances surrounding

the Paris Commune. The wartime emphasis

on austerity, the hardships of the Prussian siege, and a newfound sense of

solidarity between social classes, gave rise to a simpler and more practical

silhouette, as a matter of necessity and patriotism. Upon the declaration of the Third Republic,

the bustle’s cylindrical shape served as a pseudo-Classical symbol, and thus a

celebration of republicanism, and the ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

A climate of political fear arose at the formation of the Commune, and in

the chaos of the months that followed, women were bombarded with conflicting

images of the feminine ideal. As a

matter of political prudence, fashionable women were forced to drastically

alter their manner of dress in hopes of avoiding persecution. The Commune embraced the rhetoric and

symbolism of the Terror, and idealized the simply dressed Marianne. The Versaillais troops were also feared by

Parisians, as they moved through the city killing and arresting citizens at

random. The frequent and vivid, though

fictional, reports of les petroleuses captured the imagination of a

fearful city. The vitriolic accounts of

the Communardes, especially the focus on their unnatural and unwomanly

behavior, precluded the wearing of too-simple clothing, and made necessary the

accentuation of the female form. The

bustled skirt may be interpreted as the response of fashionable Parisian women

to the intense three-fold political

pressures of 1870 and 1871: the narrowed skirt as a wartime rejection of

opulence, the cylindrical shape as a celebration of republicanism, and the

padded bustle as an attempt to appease both the Communards calling for

revolution, and the Versaillais demanding traditional femininity.

Ancient Greece, 1800, and 1876

[1] David A.

Shafer, The Paris Commune (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 8-9.

[2] Octave

Uzanne, Fashion in Paris: The Various Phases of Feminine Taste and

Aesthetics from the Revolution to the End of the XIXth Century (London:

William Heinemann, 1901), 128-130.

[3] Ibid.,

130.

[4] Ibid.,

133.

[5] Ibid.,

130.

[6] Ibid.,

130-131.

[7] Ibid.,

131.

[8] John

Milner, Art, War and Revolution in France 1870-1871: Myth, Reportage, and

Reality (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 9-11.

[9] Shafer,

20-21.

[10] Uzanne,

147.

[11] Ibid.,

144.

[12] Milner,

103. Landing the Wounded at Pont d’Austerlitz, Paris, 1871. Wood

engraving, 31x46 cm. Illustrated London News, 21 January 1871.

[13] Gay L.

Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press, 1996), 14-15.

[14] Le

Moniteur de la Mode, (Paris: Goubaud, 1 April 1871), 11-12.

[16] Le

Moniteur, 12.

[17] Shafer,

30.

[18] Ibid.,

34.

[19] Gay L.

Gullickson, Unruly Women of Paris: Images of the Commune (Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 1996), 14-15.

[20] Shafer,

47.

[21] Ibid.,

48.

[22] Ibid.,

47.

[23] Milner,

94. “Inside Paris: A sale by Auction in the Fish Market (Sketch by Balloon

Post),” 1870. Wood engraving, 22.4x23.6 cm. Illustrated London News, 3

December 1870.

[24] Milner,

104. “The Market for Dogs’ and Cats’ Flesh, Paris,” 1871. Wood engraving, 22.4x24

cm. Illustrated London News, 28 January 1871.

[25] Shafer,

47-48.

[26] Ibid.,

49-50.

[27] Ibid.,

50.

[28] Ibid.,

51.

[29] Ibid.,

48-51.

[30] Milner,

110.

[31] Shafer,

54.

[32] Ibid.,

56.

[33] Ibid.,

54-57.

[34] Ibid.,

58-61.

[35] Ibid.,

59.

[36] Ibid.,

59.

[37] Ibid.,

62.

[38]

Gullickson, 19.

[39] Shafer,

75-77.

[40] Milner,

154-157.

[41] Shafer,

83.

[42] Milner,

161.

[43] Shafer,

91-92.

[44] Ibid.,

97.

[45] Milner,

180.

[46] Shafer,

97-98.

[47]

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robe a la francaise, ca 1765.

2001.472a, b.

[48] Ibid., Robe

volante, ca 1730s. 2010.148.

[49] Ibid., Robe

a la francaise, ca 1785. C.I.65.13.2a-c.

[50] Ibid., Robe

a l’anglaise, ca 1787. C.I.66.39a, b.

[51]

Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun. Comtesse de la Chatre (New York: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 1789), 54.182.

[52] Le

Moniteur, 11.

[53]

Metropolitan Museum, Robe a la polonaise, ca 1793. 34.112a, b.

[54]

Metropolitan Museum of Art. 100 Dresses: The Costume Institute (New

York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010), 18.

[55] Ibid.,

18-19.

[56] Uzanne,

148.

[57] Milner,

20. Paul Klenck, La Montijo. Musee d’art et d’histoire, Saint-Denis.

[58] Ibid.,

62. The Revolution in Paris: Celebrating the Proclamation of the Republic on

the Boulevard des Italiens, 1870. Illustrated London News, 17

September 1870.

[59]

Francois Bonneville. French Women Who Have Become Free. (Paris, 1792).

4232.2.42.73 <waddeson.org.uk>

[60] Paul

Klenck. La Commune: Paschal Grousset. (Paris: 1871), Victoria and Albert

Museum, E.2021-1962.

[61] Paul

Klenck. La Commune: Cournet. (Paris: 1871), Victoria and Albert Museum,

E.2022-1962.

[62] Paul

Klenck. La Commune: Felix Pyat. (Paris: 1871), Victoria and Albert

Museum, E.2013-1962.

[63] Georges

Pilotell. Le Vrai Pere Duchene. (Paris:1871), Northwestern University

Special Collections, 1-983.

[64]

Gullickson, 68.

[65]

Gullickson, 68.

[66] Ibid.,

69.

[67] Milner,

31. Gustave Dore. La Marseillaise, 1870. Musees d’art moderne et

contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg.

[68] Milner,

61. Paul Klenck. The Departure of the Empress Eugenie (4 September 1870), 1870.

Musee d’art et d’histoire, Saint-Denis.

[69] Milner,

127. Cham. Oh no! Prussia has not yet completely killed her! It is still not

time to come to her aid, 1871. Musee du Louvre, Paris.

[70] Milner,

131. Honore Daumier. The Bordeaux Assembly- Who will take the knife?, 1871.

Le Charivari, 16 February 1871.

[71] Georges

Pilotell. L’executif, 1871. Victoria and Albert Museum, E.2214-1962.

[72] Milner,

150. Honore Daumier. The Chariot of State in 1871, 21 April 1871.

[73]

Faustin. Thiers et la Republique, 1871. Northwestern University Special

Collections, 1-1003.

[74]

Northwestern University Special Collections, 1-1015; Wikimedia Commons.

[75] Milner,

184. Gustave Dore. La Republique, 1871. Musees d’art Moderne et

Contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg.

[76]

Gullickson, 3-4.

[77] Milner,

161. A Street Incident in Paris, 1871. Illustrated London News, 10

June 1871.

[78]

Gullickson, 84. The Triumph of the Monarchy, 1871. Bibliotheque

Nationale.

[79]

Gullickson, 52.

[80]

Gullickson, 4-5.

[81]

Gullickson, 4.

[82] Milner,

162. Dupendant. The Defence of the Commune, 1871. Musee d’art et

d’histoire, Saint-Denis.

[83] Shafer,

98-99.

[84] Shafer,

158-159.

[85]

Gullickson, 188. The End of the Commune: Execution of a Petroleuse, 10

June 1871. Bibliotheque Nationale.

[86]

Gullickson, 174.

No comments:

Post a Comment